[ad_1]

Given the profound importance of the Hundred Years War – conducted between 1337 and 1453 between England and the French – on the subsequent history of both combatants, and indeed on much of Western Europe, it is astonishing that its details are so little taught, and therefore so little understood. At the conclusion of the fifth and final volume of his unsurpassed, and probably unsurpassable, history of the war, Jonathan Sumption observes that “defeat proved to be as decisive for the future of England as victory was for that of France”. He adds that “if Henry V and the Duke of Bedford had achieved their ambition of uniting France and England under the house of Lancaster… England’s subsequent history would have been very different.”

Bedford was Henry V’s younger brother, and became Protector – effectively Regent – when the King died in 1422, the Throne passing to the nine-month-old heir, Henry VI, who would have no real influence on English policy until the late 1430s. This was just seven years after Agincourt, the stunning victory that seemed to cement English power in northern France. England’s lands in France, and the declaration by English kings that they were kings of France too, necessitated the military campaigns that ran through almost two-thirds of the 14th and over half of the 15th centuries. It was in support of his contention to be King of France that Edward III had started the conflict, and a succession of English triumphs had only reinforced the country’s determination to maintain its French lands. Sumption has catalogued this in remarkable detail in the four preceding volumes; this one describes the end of the affair, with only the outpost of Calais remaining, to be lost by Mary Tudor in 1557.

As usual, Sumption’s writing is rich in military and political detail. He does not overburden the reader with his own conclusions, but offers them when he has a deep insight to share. He gives his readers enough evidence from which they can draw their own conclusions. From his narrative, it becomes clear that there were three main reasons for the decline of English power in France.

The first was financial; the second was a question of leadership; the third was logistical. Even in the 1420s, when the English military campaign was going successfully (exemplified by the rout at Verneuil of the forces of the Dauphin, and those of Scotland and Milan, in 1424), a shortage of funds put in jeopardy the ability to pay existing soldiers and recruit new ones. Over the next 30 years, the prosperity of England, founded in that era on the wool trade and with substantial markets in Flanders and the Low Countries, went into serious decline. An agricultural depression began in the 1430s that lasted for the rest of the century. It was not an ideal situation in which to fight an expensive, if sporadic, war; and within a couple of years of the defeat in France, the factionalism and disquiet that had helped undermine English unity in the closing years of the conflict sparked a new one: the Wars of the Roses.

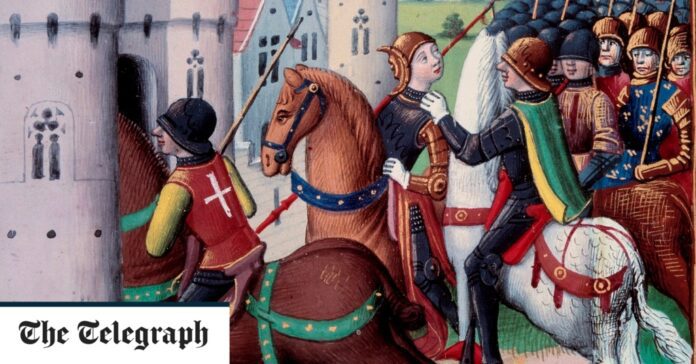

England triumphed at Verneuil not least because of the military abilities of the Earl of Salisbury. His death in 1428 marked the beginning of the end. The next year Joan of Arc emerged, and matters took a further turn for the worse. Sumption paints her without sentimentality as a religious maniac with no grasp of the realities of conducting warfare; but he also describes superbly the tenor of medieval French society, with its deep religiosity, that not only won her a popular following but enabled her to talk the Dauphin’s commander round to her ideas of how to proceed against the English.

[ad_2]