[ad_1]

It’s the three-part ITV drama which has gripped the nation for scenes depicting the realities many frontline NHS doctors faced at the height of the pandemic.

Yet, despite Breathtaking’s characters being entirely fictional, the tear-jerking plot is supposedly anything but.

It is heavily based on the day-to-day life of Dr Rachel Clarke, a palliative care doctor who volunteered herself to the NHS frontline for almost a year and was tasked with treating patients dying of Covid on virus-riddled wards.

Although dramatized and including scenes that did not directly affect her, Dr Clarke insisted that it was ‘very important’ everything on screen happened to a real patient or member of NHS staff.

The Oxford-educated former journalist, who retrained as a doctor in the late 1990s, hopes the series, criticised as being a polemic that ‘forgets storytelling in favour of politics’, helps NHS medics who worked through the pandemic ‘feel seen’.

And, so she claims, her intention was only to challenge the Government’s ‘downright lies’ that the NHS was ‘coping’.

Dr Clarke repeatedly criticised ministers, particularly ex-PM Boris Johnson and then-Health Secretary Matt Hancock, at the height of the Covid crisis.

Some of her scathing social media posts – made during the darkest months of the entire pandemic – attacked the ‘breathtaking incompetence’ of the testing scheme and the ‘irresponsible’ decision to ease lockdown while cases were soaring.

Breathtaking is adapted from a memoir of the same name, authored by NHS palliative care doctor Dr Rachel Clarke. Pictured, Dr Clarke appearing on Lorraine yesterday

Dr Clarke (pictured in 2016) qualified in 2009 and began working as a junior doctor, covering areas ranging from paediatrics and emergency medicine to cardiology, before making the decision in 2016 to dedicate her career to palliative care

So far, Breathtaking, co-written by Line of Duty creator Jed Mercurio and Prasanna Puwanarajah (both of whom are ex-doctors themselves), has shown a heartbreaking scene of a patient being left to die in the back of an ambulance because of rules that prevented medics from giving CPR over infection fears.

Tonight’s second episode shows Dr Abbey Henderson, played by Downton Abbey star Joanne Froggatt, having to turn off the life support of a beloved colleague who was killed by the virus.

Born in 1972, Dr Clarke grew up in rural Wiltshire, with her GP father Mark and nurse mother Dorothy, as well as her twin Sarah and brother Nick.

She studied philosophy, politics and economics at Oxford University, graduating in 1993 before embarking on her career as a broadcast journalist.

Travelling the world, she produced and directed current affairs documentaries for Channel 4, covering Al Qaeda, the Iraq War and the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

However, she decided to make a career change in 1997 in the aftermath of Princess Diana’s death.

She had been asked to call the grandmother of Diana’s bodyguard, who had been badly injured in the car crash in Paris, which Dr Clarke said left her feeling ‘shame’.

Dr Clarke then took the decision to pursue a career in medicine.

She began studying A-level chemistry and biology at night school and applying to medical schools alongside her day job as a broadcast journalist and secured a place at University College London.

Eventually, aged 29, she began studying medicine in 2003 alongside freshers, most of whom were a decade her junior.

‘Sitting in the front row of the lecture theatre on day one, I knew this was what I was meant to do,’ Dr Clarke said.

Two years into the course, Dr Clarke moved to Oxford University to continue her degree and be with her partner Dave, a former fighter pilot who now works in commercial aviation.

The pair went on one date after being set up by her flat-mate while Dr Clarke was still working in TV and Dave was about to set off to fight in the Gulf War. Months later, he emailed her after an aircraft had been shot down, killing two people, saying that he had been inspire to seize the day as a result.

The couple have now been married for 19 years and have a son, Finn, 17, and daughter, Abbey, 13.

While at Oxford, Dr Clarke believes she became the first medical student to have a baby while studying, taking a year out to raise Finn.

She qualified in 2009 and began working as a junior doctor, covering areas ranging from paediatrics and emergency medicine to cardiology, before making the decision in 2016 to dedicate her career to palliative care.

Speaking of her decision to choose end of life care, Dr Clarke once told of hearing a consultant during her training refer to sending a patient to the ‘palliative dustbin’.

She told the British Medical Association (BMA)’s Inspiring doctors podcast: ‘I was so disgusted by that. I couldn’t believe a doctor could treat a human life with such contempt.

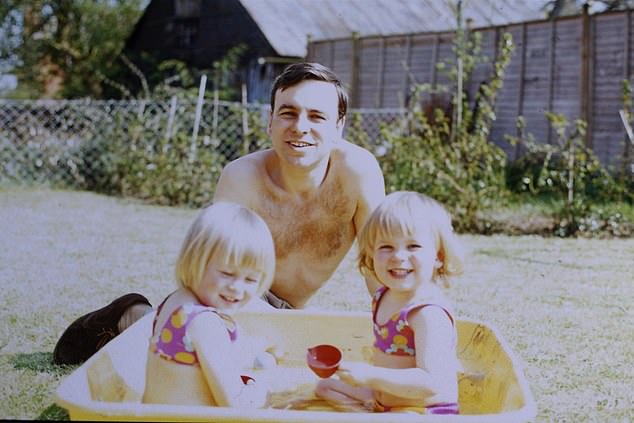

Rachel (left) aged three with her dad and twin sister Sarah, 1975

Rachel – graduating as a doctor in 2009 – with her parents and sister

Rachel with her father Mark in November 2017, just weeks before he died

‘I realised that these patients were no longer interesting to certain doctors because we didn’t any longer have the capacity to save their lives.

‘But to me, they were still human beings and in fact, they needed us even more than maybe other patients, precisely because they knew they were dying.’

Dr Clarke has spoken about her role as a palliative medic at Katharine House Hospice in Oxfordshire, where she has helped a terminal patient join friends on a Ibiza holiday and sneaking a prize-winning bull of another patient, a farmer, into the hospice garden.

It was in 2016 that Dr Clarke became a prominent voice among junior doctors. She said she was ‘acutely politicised overnight’ by former Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt’s contract for junior doctors that extended their working week to seven days, reducing premium pay rates previously offered for weekend work.

In an interview that year, she said she was ‘livid’ with the now Chancellor for pushing her ‘into a corner’ and forcing her to strike, accusing him of manipulating doctors and lying.

That strike lasted for the first four months of 2016.

Before those walkouts, there had only been one other strike in the previous 40 years, which took place in 2012.

Ongoing NHS strikes, which include junior doctors, have seen around 1.4million appointments and operations cancelled since October 2022. The medics are taking to picket lines on Saturday, as part of five days of action.

Dr Clarke became well known on Twitter, routinely criticising politicians and warning of pressures on the NHS. She said she has been called names such as ‘Hitler and Satan’ and accused of being a ‘child abuser’ as a result.

However, she has repeated BMA claims on that platform that junior doctors’ starting salary is £14.09 per hour, claiming it is less than workers make in Pret A Manger.

This is despite the charity Full Fact noting that the sum represents just the hourly basic pay for the lowest-ranked doctors, who make up just a tenth of all junior doctors. It also doesn’t include additional pay for working nights and weekends.

Dr Clarke has also hit out Health Secretary Victoria Atkins for referring to junior doctors as ‘doctors in training’, as if they’re ‘still wearing stabilisers’ — despite the BMA also using the term.

The first of her three Sunday Times bestselling non-fiction books, Your Life in My Hands: A Junior Doctor’s Story, was published in 2017, detailing her experience as a young medic.

Her second novel, Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love, Loss and Consolation, was published in 2020 and chronicles her time spent caring for her father following his bowel cancer diagnosis in September 2016. He died just 15 months later on Boxing Day the following year.

Speaking to the Mail at the time, she said: ‘Before my father died, I thought of myself as an empathetic doctor.

Dr Clarke lives with her husband, Dave, and her two children, Abbey, 10 and Finn, 14

Dr Clarke became well known on Twitter, routinely criticising politicians and warning of pressures on the NHS. She said she has been called names such as ‘Hitler and Satan’ and accused of being a ‘child abuser’ as a result

‘I believed I was “good” at dealing with death; I felt I understood what patients and families were going through, and how best to communicate with them.

‘Losing Dad taught me how little I truly knew about grief and loss. It gave me a new insight into the emotions of the people I work with; it humbled me.’

Her latest book, Breathtaking, formed the basis for the ITV show, and logged her experience working on the NHS frontlines during the pandemic, where she said up to eight Covid patients were dying on a ward each day.

It is based on a diary she kept during the pandemic, which she claimed she didn’t plan to become public but felt she had to share due to the Government’s ‘misinformation and spin’ that the NHS was coping during the pandemic and there was enough ventilators for the patients who needed them.

‘All of that was completely dishonest,’ she told The Guardian.

The show cuts archive footage from the pandemic, including briefings from Boris Johnson and Matt Hancock, with the experience on the wards.

Dr Clarke said she wants NHS staff impacted by Covid ‘feel seen’.

She said: ‘One of the main themes of the drama is truth telling and the matter of whose story, whose truth is heard and whose story is silenced.

Later the same episode — the second to air — features an equally upsetting scene which TV critics have described as ‘so realistic it will break your heart’. The first episode saw young healthcare assistant Divina start to show signs of having Covid when caring for patients. Minutes later, Divina – of an Hispanic background – is stretchered into her own ward (pictured) after deteriorating rapidly. She is whisked into intensive care and placed in an induced coma

‘So, the entire unfolding of the story inside the hospital is one that has not been told very loudly on a public stage.

‘I wanted to address that gulf between the Government’s public narrative of Covid and the unfolding reality within the NHS because partly that gulf has a huge human impact.’

She added: ‘I hope that when NHS staff watch the series they feel seen. I hope they’ll think: “That’s me, that’s what I went through. That is my testimony and now the public knows what it was like.”‘

Dr Clarke has compared hospitals during the pandemic to a ‘wartime crisis situation’.

One of the ‘most horrific things’ about the pandemic was that many patients arriving in hospital ‘were never ever going to see another unmasked human face again’, she said.

NHS staff at her trust also found themselves trying to save the lives of their own colleagues. She said: ‘I remember when the first individuals in my Trust died from Covid. I was walking along outside the hospital and I felt like I had been punched almost in the gut by the news and I just burst into tears.

‘I didn’t know them personally but they felt like part of our NHS family and they had died trying to do their best for patients.’

And, writing for the Guardian in the wake of the Partygate scandal, she authored a piece titled: ‘While Boris Johnson partied, I helped a child put on PPE to see his dying dad’.

As well as being a palliative medic and author, Dr Clarke has also set up a charity, Hospice Ukraine, to support the development of end-of-life care in the war-torn country.

She was inspired to do so following a trip to west Ukraine, where she trained medics. It has raised more than £65,000 to provide training, equipment and medicine.

Dr Clarke’s next book, The Story of a Heart, a novel about a child who receives a heart transplant, will be published in September.

[ad_2]