[ad_1]

Anthony Stokes is facing a stretch of time in prison when we meet and is superficially philosophical about that.

‘It’s not going to break me, going in there,’ he says – and by the time we reach this question of the criminal system catching up with him, he has casually related the kind of details that give cause to imagine no environment would hold any fear for him. Acquaintances with the paraphernalia of IRA paramilitaries as a child. The uncompromising figures who would approach him in Glasgow, where he was a star for Celtic, asking if his adoptive father, a Real IRA man, might furnish them with weapons. Rangers fans offering him out of his car to fight in central Glasgow. Stokes obliging them on one occasion.

Yet there’s something about him which tells you that the prospect of going behind bars is not quite the breeze he claims. And sure enough, the appointed day on which he says he will return from Dublin to Glasgow, where he absconded last year after jumping bail, comes and goes. So does the next appointed day. And the next. Until, finally, last month, he took a ferry from Dublin and presented himself at a police station, where he was held in the cells.

‘Will be out of contact for a short period. Speak sooner rather than later,’ his last message to me reads – and after that, things do not go quite as he had anticipated. He is walked, handcuffed, into court the next day. A judge, Sheriff Diane Turner, sends him to HMP Addiewell, between Glasgow and Edinburgh, for at least 30 days – more than he expected – ahead of a sentencing hearing, later this month, on charges he has already admitted to.

Entirely fair, because Stokes has shown a very casual disregard for the need to answer for those charges. A few hours sitting in his extremely easy company, in Dublin, listening to him relating the story of an extraordinary football life, belie five years of chaos and disregard for the legal system which have been unattractive to say the least. His conduct after splitting with his former partner, Eilidh Scott, during a period playing club football out in Iran in 2018, was not acceptable. Only now, six years on, is he is paying the price.

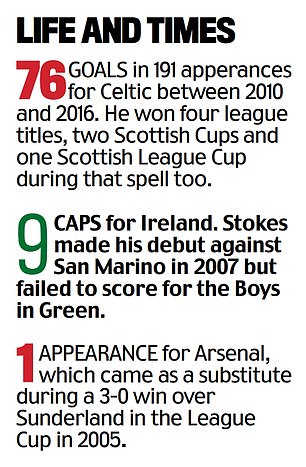

Anthony Stokes experienced the heady heights of success with Celtic but his life off the pitch has been checkered by chaos

The Dublin-born striker began his career as a youth player at Arsenal after moving from Ireland

The 35-year-old is awaiting sentencing this month at HMP Addiewell in Scotland for a historic stalking offence

That split, he says, was personally distressing enough for him to abruptly leave the Iranian club, Tractor, and the lucrative salary he commanded there, to return home to Scotland, leading the Iranians to go after him for a breach of contract. But it also prompted him to send a barrage of messages to Ms Scott and her mother and to receive a non-harassment order forbidding him to contact them, which he breached. Stokes’ very semi-detached approach to the judicial system after behaviour he accepts was wrong demands a time to take stock, at least.

Some will not empathise with an individual for whom poor behaviour has been an intermittent part of life. But there is some story to tell and lessons for him to impart to the next generations of players if Stokes, who left Ireland for Arsenal, aged 14 and still very much a boy, can now, aged 35 and retired, reflect a little and belatedly grow up.

He was one of those prodigious young players for whom there is no time to enjoy normal adolescence, as a group of top-flight English clubs queued up to sign him in the early 2000s. He had played for the renowned west Dublin club, Cherry Orchard, then the Shelbourne team, with its links to Manchester United, which has sent many young players over the water. United wanted to sign him very badly and gave him the Sir Alex Ferguson treatment when he was contemplating his move.

Stokes describes stepping into Ferguson’s office with his father for the conversation which United were convinced would seal his signature, given the additional influence of the club’s academy manager John Devine, an Irish former player and manager. It says something about the teenager’s assuredness, even then, that he decided to ask for Ferguson’s autograph, though realised he had nothing to ask him to sign.

‘I didn’t want to ask him, ‘can you get a bit of paper to sign?’ So, my dad had a five-pound note and I just said, “Can you sign that?” I’ve still got it in the house.’

Stokes was courted as a youth prospect by both Sir Alex Ferguson (left) and then-Liverpool boss Rafa Benitez (right)

In the end he was won over by Irish ex-player Liam Brady who was running Arsenal’s academy

Liverpool had heard about Stokes, too. There was a phone call to the family home on a Christmas Day around that time from their then manager Rafael Benitez.

‘It’s like, you’re 13, 14 at this stage you’ve got the Liverpool manager on the phone,’ Stokes says. ‘He said, “I just wanted to wish your family a Happy Christmas. We’ve been in contact. And hopefully I’ll be seeing you soon.” All my family were Liverpool fans.’

It was a classic Benitez manoeuvre. But though Stokes’ heart had been initially set on United – ‘I was a massive United fan but I only followed United because of Roy Keane,’ he says – it was Arsenal he chose, because of the influence of Liam Brady, the legendary Irish player running the academy for Arsene Wenger at that time.

Brady’s close connection with the Dublin District Schoolboys’ League, convinced him that Stokes was one for Arsenal, where Wenger had him mix with the first team. ‘They brought me over, I went on a trial, they brought me back and Wenger just said, “Look, I’m going to train you with the first team,”’ Stokes relates. ‘I trained with them for a full session at 14.’

For a boy who had seemed to spend all his formative years trying to bunk off school, this move sounds heaven-sent. But his yearning for Ireland which followed fits a pattern which so many young Irish prodigies, from Adrian Doherty to George Best, have experienced across the water.

‘You go to Arsenal, you’re on a youth training scheme, you’re getting 180 quid a week,’ he explains. ‘You then go to sign your pro-contract. I think it was on 2,500 or 3000 a week – at 17. But I was back in Dublin every weekend. I didn’t want to be in London. I genuinely would’ve given up football.

‘I hadn’t been too keen on school, even though I’d done quite well academically and was quite good. But I dunno… once I went over there, I missed school. I just missed my day-to-day routine at home. I missed my mates. I just missed my little cocoon.’

There had been no cocoon of any kind during some terribly inauspicious early years in which there were genuine fears for his health and development. His mother, Ann, had handed him, as three-year-old, to her sister and brother-in-law, Joan and John Stokes, in 1991 because she was unable to bring him up because of a heroin dependency, which seems to have affected his neonatal health. A heroin-addicted mother who carries a baby exposes the child to the opioid in a way which can cause withdrawal symptoms after birth.

‘The heroin epidemic in Dublin went back to the ‘80s and it was still rife at the time,’ Stokes says. But his adoptive parents moved to London with him and were employed by Arsenal to act as foster parents in a house for young players at Cockfosters.

His adoptive father had been born and raised in the staunchly Republican city of Cork, was steeped in the IRA’s cause which he would subscribe to long years after the Troubles were over, and he also seems to have left Ireland with mixed feelings.

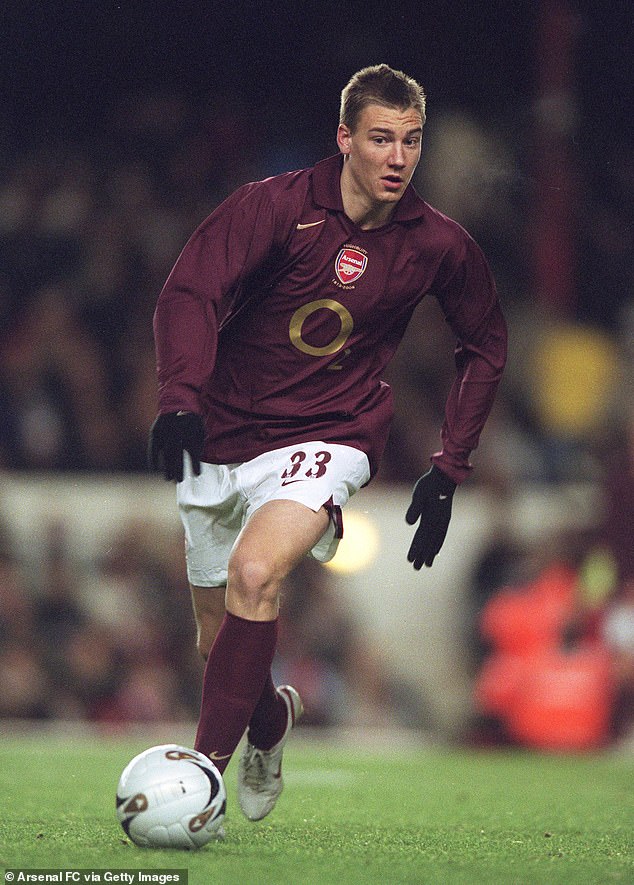

Stokes came of age in north London alongside a young Nicolas Bendtner (pictured in 2005)

‘He had gone back to Trinity College (Dublin) as a mature student to do a psychology degree which he was three years into and he ended up leaving it,’ says Stokes. ‘I think that was something that he really wanted to follow through with.’

Stokes was initially so unhappy in London that he told Brady this life wasn’t for him and Arsenal suggested he go home for a few weeks and think things over. His parents’ pastoral responsibilities for the other Arsenal boys meant that they would stay in London, at times, while he took the ferry home. But it was those Arsenal digs and the company he found there which helped him along the way when he returned.

Among the residents were Johan Djourou and a young Nicolas Bendtner, who had brought his vast self-confidence from Copenhagen, for a shot at stardom.

Bendtner’s cars made more of a mark on North London than his football. ‘I went out and got a C-class Mercedes which was a bit flashy,’ Stokes says. ‘But Nick came into training with an 80 grand Audi A6, blacked out windows, spinners on the wheels. That was Nick. He was himself. His own man. And he had all the attributes. But he was a bit peculiar.’

Bendtner didn’t really make it, though he at least had some Arsenal moments to remember. Stokes came on two minutes from the end of a Carling Cup game against Sunderland in 2005 – a 3-0 win – and never played again.

‘I thought I’d done quite well,’ he says. ‘I was regularly in the reserves about 15, 16. But by that stage you’re looking at that team – you’ve got Thierry Henry, Robin Van Percie, Rayes, Bergkamp – the list of strikers went on. Jeremie Aliadiere couldn’t get a game in the reserves, never mind for the first team.’

Desperate to play, he went on loan to Falkirk (‘I hadn’t a clue where it was’), scored a lot of goals and would have signed for Celtic, had not Keane, then managing Sunderland in the Championship, intervened and called him. ‘Can I just ask you one thing?’ Keane asked him. ‘Will you have a think about it and call me back.’ Stokes’ father looked at his adoptive son, saw the liking for girls, fast cars, the Funky Buddha club in London’s Berkeley Square, and thought Keane was the man to instil the discipline he needed.

A move to Sunderland was prompted by a call from then-head coach Roy Keane

But his arrival at Celtic sparked the purple patch of his career, which saw him score 58 times in 135 games

To some extent, he did. ‘He wouldn’t hammer you for night out,’ Stokes says of Keane, neglecting to remember the manager’s observation that Sunderland’s Glass Spider nightclub was his downfall and that he ‘could be a top, top player in four or five years or he could be playing non-league.’ He scored one Premier League goal for Keane, against Derby, but it was at Celtic – reached by way of a couple of loan deals and a brief move to Hibernian – that he found the success which had always eluded him.

He and manager Neil Lennon’s volatile relationship did not get in the way of a great six years in which Stokes scored 58 goals in 135 games and wrote himself into Celtic history. There were some indelible moments. An over-the-shoulder volleyed goal at Hibs. A hat-trick in the 9-0 annihilation of Hibs. A stellar display in the 2013 Scottish Cup final. But his arrival at a club with such a distinct Irish Catholic identity brought links back to the Republican cause in Dublin which did not help Scottish football’s attempt to bury sectarianism one bit.

Stokes’ father didn’t help. He owned a bar in Dublin – The Players’ Lounge – which was frequented by members of the Real IRA, the dissident Republican paramilitary group. It was there, in 2011, that Stokes snr was ordered to take down a banner declaring that the Queen was not welcome, ahead of her visit to the city. His son’s role as a Celtic striker gave this huge publicity.

‘My dad mentioned to me, “I’m going to put a banner up,” Stokes says. ‘And I thought he meant maybe over the bar in the pub. But I woke up the next day – I think we were playing Hearts – and it’s a 60-foot banner with a picture of the Queen’s head, saying, “As long as the British Forces are in Ireland, she and her family are not welcome in this pub.”

‘I don’t know if that’s even trying to be funny or what, but obviously it’s all over the papers in Scotland and I’m getting it left, right and centre. The Rangers fans. Messages off the UDF (Ulster Defence Force) listing details of a flight I was taking and threatening to shoot me. I had to go to the police over that. It was getting very hostile. I mean – I support my dad a hundred percent, but for f*** sake mate, come on! I’m up to my neck and as it is! I don’t need any of this!’

But Stokes’ father’s involvement with Republicanism has extended way beyond publicity stunts which might, or might not, have been him ‘trying to be funny.’ His Real IRA connections positioned him at the centre of a vicious gangland battle with a Dublin crime cartel throughout his son’s time at Celtic. Stokes snr’s associates included the leader of the Dublin brigade of the Real IRA, Alan ‘The Model’ Ryan, who was responsible for two murders before he was shot dead in cold blood by an assassin who despatched six shots from a Glock handgun.

Stokes’ father John put up an inflammatory banner ahead of Queen Elizabeth II’s state visit to Ireland in 2011

The player fanned the flames of controversy when he posted a tribute to late Real IRA brigade leader Alan Ryan

Stokes attended a tribute night for Ryan in Dublin and tweeted condolences about his death, to the bewilderment of Lennon and a Celtic management who disciplined him. ‘I am not going to moralise to him, but you cannot damage the reputation of the club,’ Lennon said of Stokes’ decision to legitimise a gangland killer.

Stokes stands by those decisions. ‘He would’ve been around my dad every day,’ he says of Ryan. ‘He was the leader of that group. I knew him well. To me, he was a normal guy. I would also be sympathetic to my dad’s beliefs about Irish Republicanism. It was a different era 30 years ago, where Catholics in the North didn’t have the same civil rights. Treat people equally, fair enough, but you put a dog in a corner along if it’s going to bite you.’

So many who once felt that grievance have moved on and helped shape the modern, progressive Ireland and Northern Ireland – free of violence. Stokes’ father has not. He was steeped in the Republican fight from his childhood days, in Cork, when men with revolvers would fetch up at the house. That was passed down to Stokes, too. He describes days as a boy when ‘someone might pull up a car in outside and you might see tools’ inside. ‘You kind of get normalised by certain things.’

Stokes father has not shed the association with violence. He stood trial on charges of extortion and blackmail – a case which collapsed. Neither, in his own way, has Stokes. A year after leaving Celtic, he was convicted of head-butting an Elvis impersonator at a pub in Dublin.

Stokes describes with some alacrity taking on the Rangers fan who invited him out of their cars to fight. ‘This fella pulls up, Rangers top on, hat and all. He started kicking my door up. I knocked him out, clean out and left him on the bonnet.’

The ex-player is keen to draw a line under the three years since walking away from the sport

Stokes’ relationship with Eilidh Scott came to an end during his spell with Iranian club Tractor

And then came the text messages, sent to his ex-girlfriend as he looked to extend his career in Iran. He learned of the split with her while out there, he says. ‘I couldn’t get back for six weeks because we had Asian Cup games in Qatar. My head was all over the place and I knew this was going on at home.’

There have been times, these past 20 years, when the uncomplicated joys of football have taken over and life has seemed as simple as it did when the 14-year-old stepped out onto the manicured pitches of London Colney. His face brightens as he journeys back in his mind to a Saturday afternoon at Hampden in May 2016 when he, on loan at Hibs from Celtic, scored two goals in the 3-2 Scottish Cup final win over Rangers to help the club record their first triumph in that competition for 114 years. ‘Edinburgh that night was something I’ll never forget,’ Stokes relates. ‘I’ve played at the San Siro, and we’ve had Celtic Park on Champions League nights but I’ve never seen anything again.’

As we part company in Dublin, he expresses a wish to draw a line under what have been three chaotic years since walking away from football. ‘I went off the rails,’ he says. ‘All this stuff – the police charges, avoiding them, has been draining. I want to move on from it, hand myself and draw a line.’ After his imprisonment, word comes back from HMP Addiewell of Stokes having access to a gymnasium three days a week and using it. The prison’s website states an aim to make those in custody ‘address their offending behaviour and the circumstances which led to imprisonment.’

His lawyers are hopeful that he will not be sent back into custody when his case is dealt with later this month, though there are no certainties. In the meantime, Stokes can only wait there in his cell and hope. Time will tell if his resolution to change will hold when he is released back into the real world.

[ad_2]