[ad_1]

Italian parmesan producers are putting microchips in their cheese in a bid to fight off counterfeiters earning billions of euros from copycat versions.

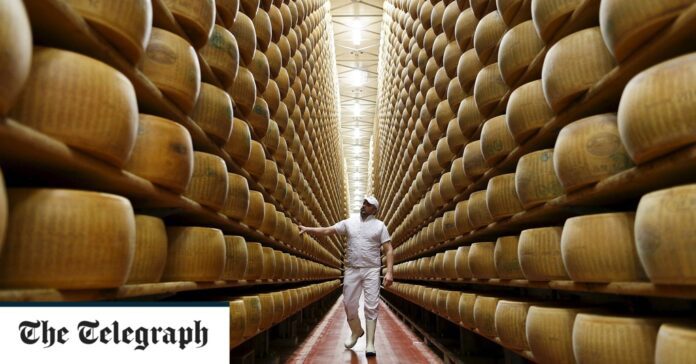

In a marriage of centuries-old tradition with cutting edge tracking technology, the consortium that governs the tight-knit world of Parmigiano Reggiano in northern Italy has been inserting the micro-transponders, no bigger than a grain of salt, into the dark yellow rinds of the hard cheese.

The tiny devices enable consumers to make sure that the product they are buying is a genuine wheel of Parmigiano Reggiano, known to most of the world as parmesan, rather than one of the many rip-offs that flood the market.

The microchips are not harmful to humans, but in any case are unlikely to be eaten because they are embedded in the outer layer of the giant cheese wheels, some of which are worth up to €1,000 (£854).

When they are scanned, the miniscule devices reveal a unique serial number that verifies the authenticity and provenance of the cheese.

They are manufactured by an American firm called p-Chip and so far have been inserted into more than 100,000 Parmigiano wheels as part of a pilot project.

Parmigiano Reggiano trade worth £2.5bn

While the trade in authentic Parmigiano Reggiano is worth around €2.9 billion (£2.5 billion) a year, sales of counterfeit parmesan are not far off, at an estimated $2 billion (£1.6 billion).

The cheese is produced to exacting standards – each wheel weighs around 40kg (88lbs) and must be matured for at least a year.

To qualify as genuine Parmigiano Reggiano, the cheese must be made in a relatively small geographical area in the north of Italy, including the provinces of Reggio Emilia and Parma, both parts of the wealthy and gastronomically rich region of Emilia-Romagna.

“We keep fighting with new methods,” Alberto Pecorari, from the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium, told the Wall Street Journal. “We won’t give up.”

Italy is fiercely proud of its food and drink products, but their global popularity attracts an army of counterfeiters keen to cash in on the appeal and kudos of the “Made in Italy” brand.

Sales of products that claim to be made in Italy but are produced elsewhere have reached a staggering €120 billion a year, according to Coldiretti, the national agricultural association.

They range from fake Parma and San Daniele prosciutto to knock-off Mortadella and cheap wine masquerading as premium vintages.

US biggest consumer

The US is the biggest transgressor, with €40 billion worth of fake Italian or “Italian-sounding” food and drink products snapped up by consumers annually.

Around 90 per cent of cheese sold in the US that purports to be Italian, from Parmigiano Reggiano and Grana Padano to mozzarella and Gorgonzola, is in fact produced in states such as Wisconsin, New York and California, Coldiretti said in a report released in June.

In Brazil there is a copycat version of Parmigiano Reggiano called Parmesao while in neighbouring Argentina, consumers buy a fake version called Regianito.

“Due to the continued rise of Italian-sounding brands, over two-thirds of ‘Italian’ food products in the world are now fake,” Coldiretti said.

In 2020, Italian police broke up a sophisticated criminal syndicate which was producing thousands of bottles of counterfeit wine and passing it off as one of the country’s most celebrated super Tuscan reds.

Two men, a father and son from Milan, were accused of buying cheap wine from Sicily, bottling it and passing it off as Bolgheri Sassicaia, which was named Wine of the Year in 2018 by the publication Wine Spectator.

Police said the men had the capacity to produce 4,200 bottles a month, bringing in around €400,000. They paid great attention to detail, reproducing a hologram on the wine labels which is meant to prevent such counterfeiting. They even found the exact same type and weight of paper used for the genuine labels, as well as identical corks. The criminal enterprise had an international dimension – the bottles came from Turkey, the labels, corks and wooden cases from Bulgaria and most of the buyers were Russian, South Korean and Chinese.

[ad_2]